What happened to the body of Jesus?

Rev'd Daniel Clark was raised in a Christian home and grew in his faith and commitment through his local church and his school's Christian Union. He gained his degree in the social sciences at Durham and studied theology at Wycliffe Hall, Oxford, and Regents College, Vancover. He is now a church leader at Christchurch, Clifton, in Bristol.

In The Tomb of God,[1] Paul Schellenberger and Richard Andrews proposed a conspiracy theory to beat them all. They suggested that Jesus’ bones were removed in the twelfth century and now lie buried in south-western France, under tons of rock. It was a bestseller, but that is no guide to its truthfulness. Full of inaccuracies and misinformation, it heaps speculation upon speculation to the point where serious scholars have dismissed it out of hand.

Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code[2] has proven to be even more popular. Translated into dozens of languages and made into a film, it is one of the biggest selling novels ever. Its central thesis — that the church has covered up Jesus’ marriage to Mary Magdalene, and that their descendants survive to this day — would indeed be the biggest cover-up of all time. But as we saw in the previous chapter, despite claiming to be accurate in all its descriptions, the book actually includes many historical mistakes, and the theories it Proposes (while being very entertaining, and grabbing many headlines) have been quashed by academics. It remains in the fiction section of the library.

If a court of law were investigating what happened to Jesus’ body, the jury would have to test the competing explanations against the evidence. That evidence was presented in chapter 6 and we saw that the legal experts pronounced it to be reliable in chapter 7, so we are now in a position to weigh the various theories, and decide which is the most plausible. I’d invite you to take your seat on the jury as the cross-examination begins.

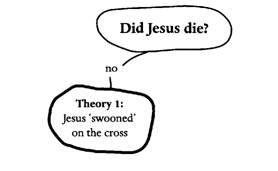

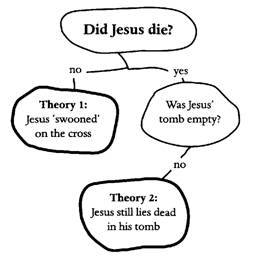

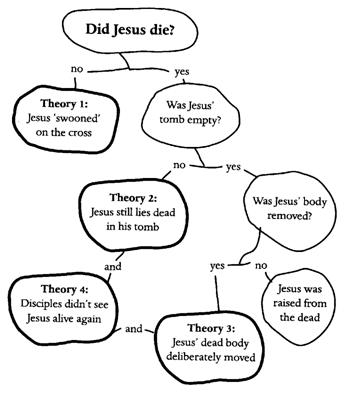

Did Jesus die? Was Jesus’ tomb empty? Was Jesus’ body removed?

There are three crucial questions that must be asked in turn: Did Jesus die? Was Jesus’ tomb empty? Was Jesus’ body removed? In this chapter, I will show how the answers to those questions spawn the various theories about what really happened to Jesus. Members of the jury may deliberate for as long as they need, but finally must give an answer to each question.

Theory 1: Jesus didn’t die, but ‘swooned’ on the cross and later revived

Barbara Thiering suggests in Jesus the Man[3] that Jesus didn’t die. Rather, he was drugged on the cross to make it look as though he had died, when in fact he had survived. Indeed, she says, so had the two people crucified alongside him (whom she identifies as Judas Iscariot and Simon Magus), even though the gospels tell us that they had had their legs broken, which would have ensured a swift end to their agony. She speculates that all three of them were put in a cave, where Simon Magus was able to give Jesus a cure for the poison he had taken on the cross — conveniently found in the spices which the women had placed in the tomb. Thus, Jesus was able to emerge from the tomb, having apparently died.

While the variations of this theory are new, the gist of it has been around for at least two hundred years. Sometimes it is called the ‘swoon theory’, as it suggests that Jesus did not really die on the cross, but merely fainted as the intense daytime heat soaked up what stamina remained after his cruel flogging. According to this general theory, the cool of the tomb helped to revive him, so that his appearances three days later were not the appearances of a resurrected man, but merely of a man who came perilously close to death but fortunately survived.

What happened next is anybody’s guess. Thiering’s book (in true headline-grabbing style) suggests that Jesus was married to Mary Magdalene, had three children, divorced her, then married again, eventually dying some time in his sixties. More reverently, the Ahmadiyya Muslim sect, who also believe that Jesus escaped from the tomb alive, suggest that Jesus died at the age of 120 in North India, being buried in Kashmir in the tomb of an unknown sheikh.

The main problem with such swoon theories it that they have to pick and choose which parts of the earliest historical records to accept, and which to ignore. Consequently, no serious academics accept these theories. One leading scholar concluded that ‘believing the accounts in the gospels is child’s play compared with believing Theiring’s reconstruction.’[4]

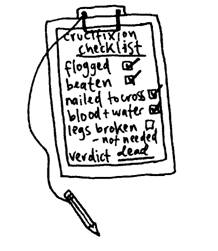

It is also very hard to accept that Jesus did not die on the cross. His Roman executioners were battle-hardened soldiers who were familiar with death, and experts in inflicting the death penalty.

Inflicting pain was their speciality, and crucifixion was a routine part of theft job. Even before Jesus was taken to the execution site, he had been severely flogged. If you have seen Mel Gibson’s film The Passion of the Christ, you may remember how severe this beating was. It was almost certainly harsh enough to leave Jesus unable to carry his own cross through Jerusalem.[5]

Evidence that supports the assertion that Jesus died includes:

As the Jewish authorities wanted the victims dead and buried before the Sabbath started, the executioners broke the victims’ legs, leaving them unable to push themselves up to breathe. Death by suffocation would have followed quickly. However, when they came to break Jesus’ legs, they saw that he was already dead.[6]

To confirm and guarantee this, one of the soldiers pierced Jesus’ side with a spear, drawing blood and water.[7] This wound would have been enough in itself to kill Jesus in his weakened state, but the flow of blood and water is medical evidence that he had already died.[8]

Jesus’ death was unusually quick, causing Pilate to double- check with the centurion that Jesus had already died. The duty centurion confirmed Jesus’ death.[9]

The execution squad had a vested interest in ensuring that Jesus was dead: it is likely that they would have suffered the death penalty themselves had they let one of their victims escape with their life.

When these factors are weighed together, by far the most logical conclusion is that Jesus died. However, if by some miracle Jesus had survived the crucifixion, the ‘swoon’ theory has further difficulties. For example:

Jesus clearly would have needed expert medical help, yet none could have come from outside the tomb because of the sealed entrance and Roman guards. There would not even have been any food or water inside the tomb. The eyewitness evidence tells us that Jesus was buried alone in a fresh tomb’[10] — not with other people who could have helped him revive!

Jesus would need to have escaped from his grave clothes. This would have been very difficult as they probably would have hardened around him into a mummy-like effect.

Jesus would need to have escaped from the tomb — somehow moving the boulder from the entrance. The boulder was far too heavy for one fit man to move, let alone a man weakened by severe flogging and failed crucifixion.

Jesus would need to have crept past the Roman soldiers who were guarding the tomb, without being noticed.

- Having escaped death by the narrowest of margins, Jesus would need to have convinced his followers that he had triumphed over death, showing no ill effects. One ardent sceptic admitted that this was ‘impossible’, saying, ‘Such a resuscitation could by no possibility have changed the [disciples’] sorrow into enthusiasm, and elevated their reverence into worship.”[11]

Theory 2: Jesus still lies dead in his tomb

Given that Jesus died, it is not unnatural to assume that his corpse remained, and still remains, in his tomb. Indeed, a BBC programme in the mid-199os highlighted the discovery in Jerusalem of a first-century ossuary (a casket for bones) with the engraving ‘Jesus son of Joseph’ on it. Also in the same tomb were ossuaries of people named Joseph, Mary, and Judah, a ‘son of Jesus’. However, these names were all very common in first-century Israel, and although the media made a big fuss about the discovery, the professional archaeologists knew that it was a bit like finding an entry for John and Jane Smith in a telephone directory. It no more proved that Jesus’ body remained in his tomb an did the Turin : Shroud.

The disciples accidentally looked in the wrong tomb

Some people suggest that Jesus’ followers Were mistaken in thinking that Jesus’ tomb was empty because they were looking in the wrong tomb. However, looking at the eyewitness evidence reveals that several different groups of people knew where the correct tomb was, and would have been able to identify it.

Mark’s biography states very clearly that Mary Magdalene was there when Jesus’ body was laid in the tomb on the Friday evening, and that she was also one of the women who went to the tomb early on the Sunday morning.’[12] To claim that her grief made her forget 1flhtbm forty-eight hours where her dear friend was buried deeply patronising!

Joseph of Arimathea is even less likely to have forgotten the tomb in which Jesus was placed, because he owned it.[13]

The Roman guards who were stationed at the tomb would not have left it once stationed there.’[14]

To suppose that the tomb was not actually empty asks us to believe that all of these groups of people got the venue wrong, despite their vested interests in getting the right tomb. For example, if Jesus’ friends and followers had got the wrong tomb, we can be certain that both the Roman and Jewish authorities would have been delighted to correct their mistake quickly.

Furthermore, if this theory was right, and Jesus was still lying dead and buried elsewhere, we would also have to find adequate explanations for the disciples’ strong conviction that they had seen Jesus alive again — which is easier said than done (see Theory 4 below). All in all, it is highly implausible to believe that Jesus’ tomb still had his corpse lying in it. A well-respected Jewish scholar reached this conclusion:

In the end, when every argument has been considered and weighed, the only conclusion acceptable to the historian must be ... that the women who set out to pay their last respects to Jesus found to their consternation, not a body, but an empty tomb.’[15]

The disciples deliberately made up the story about Jesus’ tomb being empty

Some people suggest that the disciples knew full well that Jesus’ body was still in the tomb and made up the story about it being empty. This questions the reliability of the gospels’ records, which contradicts the conclusions of the previous chapter. But there are other problems with this view as well, most of which will be expanded on later in this chapter.

Advocates of this theory would still need to find convincing explanations for over five hundred people seeing Jesus alive after his death.

The authorities would have gladly silenced the new movement by exhuming the body. That they did not is strong evidence that they could not.

It is hard to imagine that the disciples could possibly have convinced people that Jesus was alive again if they knew that he was still dead — yet they convinced thousands.

It is even harder to imagine that the disciples would have been willing to die a martyr’s death for a cause they knew to be false — yet many of them did die for their convictions. Today, suicide bombers are prepared to die for what they believe to be true (whether or not it actually is true). But no one is stubborn enough to die for what they knew to be false. In any case, such a huge cover-up would have been impossible to maintain, as Charles Colson, lawyer and special counsel to President Richard Nixon knows only too well, having been imprisoned for his part in the Watergate scandal:

Take it from one who was inside the Watergate web looking out, who saw firsthand how vulnerable a cover-up is: Nothing less than a witness as awesome as the resurrected Christ could have caused those men to maintain to their dying whispers that Jesus is alive and Lord.’[16]

No-one is stubborn enough to die for what they know to be false.

The thousands of people who converted to Christianity after the disciples started preaching about the resurrection were all Jews who either lived locally, or were visiting. One scholar comments that these people

were accepting a revolutionary teaching which could have been discredited by taking a few minutes walk to a garden just outside the city walls. Far from discrediting it, they one and all enthusiastically spread it far and wide. Every one of those first converts was a proof of the empty tomb, for the simple reason that they could never have become disciples if that tomb had still contained the body of Jesus.[17]

For all these reasons, it is most improbable that the disciples could have invented the story of the tomb being empty: it is again best to conclude that Jesus’ tomb was indeed empty by the Sunday morning. But how did it come to be empty? Our final key question is this: was Jesus’ body removed?

Theory 3: The tomb was empty because someone moved Jesus’ body

Given that Jesus was really dead when he was placed in the tomb and that all the evidence points to his tomb being empty on the Sunday morning, many suggest that Jesus did not rise to life again, but that his corpse was removed.

A variety of different groups of people, each with their own motives, have been suggested as the possible culprits.

Grave-robbers stole the body

Grave-robbing was not unknown in ancient times, and with thousands of visitors to Jerusalem for the Passover, there were bound to be more undesirables than usual. With Pilate having posted the sign ‘King of the Jews’ over Jesus’ head as he died, some might have been enticed by the (incorrect!) thought that the king’s grave would have contained riches.

There are several improbabilities with this theory:

It is unlikely that robbers would have managed to pass the professional Roman guards on duty at the tomb who would have faced severe punishment for allowing the robbers in.

Why would the robbers have stolen a worthless corpse from the tomb, and left the valuable burial cloths behind?[18] They would have been fairly incompetent thieves!

Again, an explanation would still be needed for the disciples’ meetings with Jesus after his death, and the subsequent changes in their lives.

This theory has no evidence to support it, and plenty weighing against it.

The disciples removed the body

Some people suppose that the disciples were expecting Jesus to rise again, and so suggest that the disciples removed the body to try to ‘engineer’ Jesus’ resurrection for him.

In 1992, the well-known biographer A.N. Wilson turned his attention to Jesus,’[19] and proposed a variation to this theory. Having dealt with Jesus’ life and death, Wilson suggests that he remained dead, and his disciples took his body back to Galilee for burial there. Wilson goes on to attempt to explain the rise of the Christian movement by suggesting that Jesus’ brother James reassured Jesus’ followers that it had all happened ‘according to the Scriptures’, and was in the process mistaken for Jesus himself— as his brother, there could have been a strong family resemblance It was after this case of mistaken identity that the story spread that Jesus had risen from the dead.

As we will see in a moment, there are huge obstacles to believing that the disciples could have taken Jesus’ body, but in response to Wilson’s particular theory, there are also massive historical barriers to believing that James could have been mistaken for Jesus. According to the first historians of the church, James himself was a key player in the early years,[20] and it is inconceivable that he would have let such a crucial misunderstanding linger. In any case, James is listed as one of the people to whom Jesus appeared,[21] so Wilson has to conveniently ignore that piece of historical data as well.

There are huge obstacles to believing that the disciples could have taken Jesus’ body

Wilson’s is an imaginative idea, but does not stand up to historical investigation. One scholar begins his critique of Wilson’s portrait of Jesus by saying, ‘This is, frankly, such a tissue of nonsense that it is hard to know where to begin to answer it.’[22]

So what are the other problems with the notion that the disciples moved Jesus’ body from its tomb? For starters, it is clear from the subsequent reactions of the disciples that they were not expecting Jesus to come back to life, so ‘engineering’ his resurrection would have been the last thing to enter his followers’ distraught minds.

Nevertheless, that the disciples stole the body was the ‘official’ explanation that was given by the Temple authorities. Matthew’s biography of Jesus records that some of the guards from the tomb

went into the city and reported to the chief priests everything that had happened [i.e. the empty tomb]. When the chief priests had met with the elders and devised a plan, they gave the soldiers a large sum of money, telling them, ‘You are to say, “His disciples came during the night and stole him away while we were asleep.” If this report gets to the governor, we will satisfy him and keep you out of trouble.’ So the soldiers took the money and did as they were instructed. And this story has been widely circulated among the Jews to this very day.[23]

As an explanation, it was pretty poor: the highly disciplined Roman guards faced severe discipline for sleeping on duty, and if they had all been asleep, how did they know who had taken the body?! And would they really have slept through several men shifting a massive boulder right next to them? Matthew doesn’t even bother to attack this particular explanation because it was so laughable.

But could there be any truth behind the story — could the disciples have removed the body? It is highly unlikely, for a number of reasons:

The disciples had already shown themselves to be a cowardly lot in the face of soldiers, by running away when Jesus was arrested[24] — indeed, most of them seem to have fled Jerusalem itself. Are we now to suppose that the few dejected men who remained were suddenly courageous enough to take on the professionally trained Roman guards, having watched Jesus’ gruesome execution? It is highly improbable that they would have taken on the guard, and inconceivable that they would have got past them.

If they did get past the guard, why were they never charged with the theft of the corpse, which was state property? Merely to have accused the disciples of such theft would have severely dented their subsequent popularity. That such a charge was never made indicates that there was no evidence of it having happened.

If the disciples did remove the body, but proceeded to proclaim Jesus as risen, they would have been deliberately deceiving their hearers into believing a lie. We’ve already seen that this is highly unlikely, and in any case, it does not fit well with the rest of their character. (Tacitus and Pliny, two of the Roman historians mentioned in chapter 6, both highlighted the distinctively upright morality of the early Christians.)

If a few of Jesus’ friends did steal the body, a realistic explanation of the resurrection appearances to all the other people would still need to be found (see Theory 4 below).

Personally, I find this the least persuasive of all the theories that have been produced to explain the empty tomb.

The Jewish authorities removed the body

Another group of people who might have had reason to move the body were the Jewish authorities. Maybe they wanted to move it so that Jesus’ tomb couldn’t become a shrine for his followers? Or in a kind of double-outwitting manoeuvre, maybe they thought that by moving the body, they could prevent Jesus’ disciples moving the body and claiming he was alive? But whatever their motives, is it plausible that they moved the body?

Within weeks of Jesus’ death and claimed resurrection, thousands of people were switching from a traditional Jewish belief to a belief in Jesus as the Messiah. The Jewish authorities were powerless to stop the new movement: they put the chief proponents in prison and told them to stop preaching, but when released, they just carried on.[25] Eventually, they had to resort to physical violence to try to quell the movement[26] — although even that did not work. Of all the tactics they could have tried to quash the new movement, the one that would have worked would have been the producing of either Jesus’ body or witnesses stating that they had removed and destroyed the body. That they did not do this is ample reason to conclude that the Jewish authorities did not remove the body in the first place.

The Roman authorities removed the body

A final group of people who could conceivably have moved the body were the Roman authorities. To them, the ‘Jesus movement’ obviously had political overtones, with people claiming that he was King of the Jews. The Roman authorities had as much desire as the Jewish ones to clamp down on the new movement, because they feared it would lead to a popular uprising against their brutal occupation. So maybe they moved the body — again to even safer keeping?

But for much the same reasons as if the Jewish authorities had taken the body, it is also highly unlikely that the Roman ones did. As soon as the new movement began gathering pace (which it did very quickly), they could have produced Jesus’ corpse and stopped the movement in its tracks. But they did not because they could not.

So was the body moved?

Of all the possible culprits that have been suggested for the removal of Jesus’ body, none are convincing. Admittedly, it doesn’t seem to make much sense to say that Jesus’ tomb was empty but that his body hadn’t been removed — we’ll come back to that problem at the beginning of the next chapter.

Of all the possible culprits that have been suggested for the removal of Jesus’ body, none are convincing

But quite apart from the weaknesses already exposed in these alternative theories, those who say that Jesus remained dead still have to try to discredit the eyewitness statements of those who claimed to see Jesus alive again. Again, the jury must make up their mind.

Theory 4: The disciples didn’t actually see Jesus alive again

Many people have surmised that the disciples did not actually see Jesus alive again, they just thought they did — in other words, they were hallucinating. After all, it is not uncommon for those who are grieving to think that they have glimpsed or heard their loved one after their death.

But the historical accounts we have of Jesus’ appearances do not merely involve people seeing him, they also include people touching him and eating with him.[27] Such physical contact would be impossible with an hallucination. Further, the appearances do not allow for accepted medical definitions of hallucinations for the following reasons:

Hallucinations happen to individuals, not groups, yet the gospel records tell us that Jesus tended to appear to groups rather than individuals. For example, he appeared to Cleopas and his companion; to ten of the disciples and then to eleven of them; to a group gathered for breakfast; to five hundred people at once. (The Christian leader Paul who wrote about this latter event did so while most of these witnesses were still alive — so any doubters could have interviewed them all to verify their claims.[28]) If it’s highly unlikely that two people would hallucinate the same thing at the same time, it’s impossible for five hundred people to hallucinate the same thing at the same time.[29]

Hallucinations happen to certain types of individuals. Some people say that Mary Magdalene was sufficiently emotional to hallucinate, and it is true that some people are more susceptible to hallucinations than others. But the resurrection appearances were made to a wide variety of people — men and women; nagged fishermen, wily tax- collectors, seasoned debaters and others. It is too much to suppose that all of these people were vulnerable to hallucinations. Maybe ‘Doubting Thomas’ was the least likely person to hallucinate, yet even he was very quickly convinced that Jesus had come back to life.[30]

Hallucinations happen in certain circumstances. Psychiatrists say that time of day and lighting levels affect the likelihood of hallucinations. Yet Jesus’ appearances were very varied in their nature: early morning in a garden; breakfast-time by the sea; in the afternoon in the bright sunlight; in the evening in a crowded room; on top of a mountain during the day. The wide variations in the circumstances make it extremely unlikely that the sightings could all be hallucinations.

Hallucinations tend to increase in severity over time, as the condition becomes worse, yet the historical accounts tell us that the sightings of Jesus stopped abruptly after forty days.

No-one expects to see a dead person alive again

Of course, no-one expects to see a dead person alive again — not even Jesus’ friends did. So on one of the first occasions when they saw the resurrected Jesus, it is not surprising that they assumed it was a ghost. But Jesus, knowing their thoughts, said to them, ‘Look at my hands and my feet. It is I myself! Touch me and see; a ghost does not have flesh and bones, as you see I have.’ Then he showed them his hands and feet, and proceeded to eat some fish with them.[31] Jesus’ friends might have thought to themselves that they were hallucinating at first, but because they saw Jesus several times, and because his appearances were so tangible, they soon became convinced that they were not just ‘seeing things’ — but that Jesus really had come back from the dead

Together, these factors all point to the conclusion that the appearances to the disciples cannot simply be dismissed as hallucinations.

Conclusion

What happened after Jesus was sentenced to death? We’ve examined the competing theories but all of them have been found wanting. We can be sure that Jesus did die on the cross on the Friday afternoon, yet that by Sunday morning, his tomb was empty. It is extremely unlikely that grave-robbers or the disciples could have taken the body from under the watchful eyes of the Roman guard, and even if they did, it would not explain the radical change in behaviour of the disciples. If either the Roman or Jewish authorities had removed the body, they would quickly have brought forward either witnesses or the corpse itself as sufficient proof to undermine the new movement’s claims and stop its growth ‘dead’ in its tracks — so we can conclude that neither of them moved the body. In any case, the sightings of Jesus alive after his gruesome death also need an explanation — which cannot be mere hallucination on the part of hundreds of witnesses.

Could it be that the strangest explanation of all, the one that the disciples gave, is actually true? Was Jesus raised from the dead? It is now time to assess that claim in more detail.

Real Lives

Albert Henry Ross wrote under the pseudonym Fank Morison

‘When ... I first began seriously to study the life of Christ, I did so with a very definite feeling that.., his history rested upon very insecure foundations.’ Ross was particularly dubious that the miracles really happened. He set out to write a book on the period of time immediately before and after Jesus’ death, aiming to ‘strip [the story] of its overgrowth of primitive belief and dogmatic suppositions’ [32]

However, when he came to investigate the events closely (a task he did so rigorously that many wrongly assumed he was a lawyer), he became convinced that the gospel records were reliable, leading him to the surprising conclusion that ‘There certainly is a deep and profoundly historical basis to [the statement] “The third day he rose again from the dead.”[33]

Ross became especially dismissive of the idea that the key witnesses deliberately made the story up. ‘No great moral structure like the early church, characterised as it was by lifelong persecution and personal suffering, could have reared its head on a statement every one of the eleven apostles knew to be a lie.’[34]

The book he eventually published became a classic. He tells his story in its Preface:

‘This study is . . . the inner story of a man who originally set out to write one kind of book and found himself compelled by the sheer force of circumstances to write quite another.

‘It is not that the facts themselves altered, for they are recorded imperishably ... in the pages of human history. But the interpretation to be put upon the facts underwent a change. Somehow the perspective shifted — not suddenly, as in a flash of insight or inspiration, but slowly, almost imperceptibly, by the very stubbornness of the facts themselves.’[35]

[1] Paul Schellenberger and Richard Andrews, The Tomb of God: The Body of Jesus and the Solution to a 2000-year-old mystery (Little Brown, i6).

[2] Dan Brown, The Da Vinci Code (Corgi, 2004).

[3] Barbara Thiering, Jesus the Man: A New Interpretation from the Dead Sea Scrolls (Doubleday, 1992).

[4] N.T. Wright, Who Was Jesus? (SPCK, 1992), p. 33. This book gives a detailed critique of Barbara Thiering’s work in chapter 2.

[5] Matthew 27.30—32.

[6] John 19.31—33.

[7] John 19.34.

[8] See Lee Strobel, The Case for Christ (Zondervan, 1998), pp. 198 —199 for a medical explanation of this.

[9] Mark 15.44—45.

[10] Matthew 27.60.

[11] D.F. Strauss, The Life of Jesus for the People (Williams & Norgate, 1879), vol. i, 3. 412.

[12] Mark 15.47— 16.2.

[13] Matthew 27.57—60.

[14] Matthew 27.62—66.

[15] Geza Vermes, Jesus the Jew: A Historian’s Reading of the Gospels (Collins, 1973), quoted in Kel Richards, Jesus on Trial (Matthias Media, 2001), p. 39.

[16] Charles Colson, Loving God (Marshalls, 1984), p. 69, quoted in Ross Clifford, Leading Lawyers’ Case for the Resurrection (CILTPP, 199,), p. 126.

[17] G.R. Beasley-Murray, Christ is Alive (Lutterworth Press, 1947), p. 63.

[18] John 20.5—7.

[19] AN. Wilson, Jesus (Sinclair-Stevenson, 1992).

[20] See for example, Acts 15.

[21] 1 Corinthians 15.7.

[22] Wright, Who Was Jesus? , p. 61. Chapter of this book goes into some depth explaining why Wilson’s theories on Jesus’ resurrection are not credible.

[23] Matthew 28.11—15.

[24] Matthew 26.56.

[25] Acts 4.

[26] Acts 7.54 — 8.4.

[27] For example, Luke 24.30; John 20.27; John 21.13.

[28] 1 Corinthians 15.6.

[29] See Strobel, The Case for Christ, pp. 238—240.

[30] John 20.24—28.

[31] Luke 24.36—43.

[32] Frank Morison, Who Moved the Stone? (Faber and Faber, 1930), p. 192. The most recent edition is published by Authentic Lifestyle, 1996.

[33] Morison, Who Moved the Stone?, pp. 9, 11.

[34] Morison, Who Moved the Stone?, p. 89.

[35] Morison, Who Moved the Stone?, quotes taken from Preface and Chapter I.